Tales from a chicken shop:

A Journal Entry

I had a sit down with a couple people to discuss where this project can go. After the first stage, where I introduced the project (for a recap or catch up click here). I wondered whether it could become more interactive. Yes, it sits on a public domain on a website with a weird name. But it’s still available to the world wide web. Yet, the website data tells me that there isn’t much traffic without an external influence.

This had to be dealt with.

The main objective was to make sure this project mitigates any form of ‘thick description’ (C. Geertz 1973:1), many academic texts can be filled to the brim with ‘jargon filled proses’ (L. Back 2016). I want an audience that operate outside the ‘ivory tower’ (C.S. Wilder 2013) of academia. So, what does one do when you want to operate outside the ivory tower. You go to Lewisham Centre and stroll into the Migration Museum.

The Migration Museum founded by Barbara Roche, explores ‘how the movement of people to and from Britain across ages has shaped who we are – as individuals, as communities, and as a nation.’ (Migration Museum website 2022). There are many museums across Britain. Why do I stroll into this one? Well firstly they are accessible; they have recently moved into Lewisham Shopping Centre and bring recognition to issues and ‘matter out of place’ (M. Douglas 1966: 35) the chicken shop is a part of this marginalised category. The aim of this project is to bring recognition to the ‘Otherness’ (S. Hall 1997: 225) media scrutiny has brought to the chicken shop and the people who frequent these businesses. How can this be accomplished? Well, the methodology for this stage of the project is helping me to solidify the previous methodology used in the previous stage as well as establishing a bit more “value” to the project by placing it in a “relevant” public space.

Methodology: Tran scripted Conversation

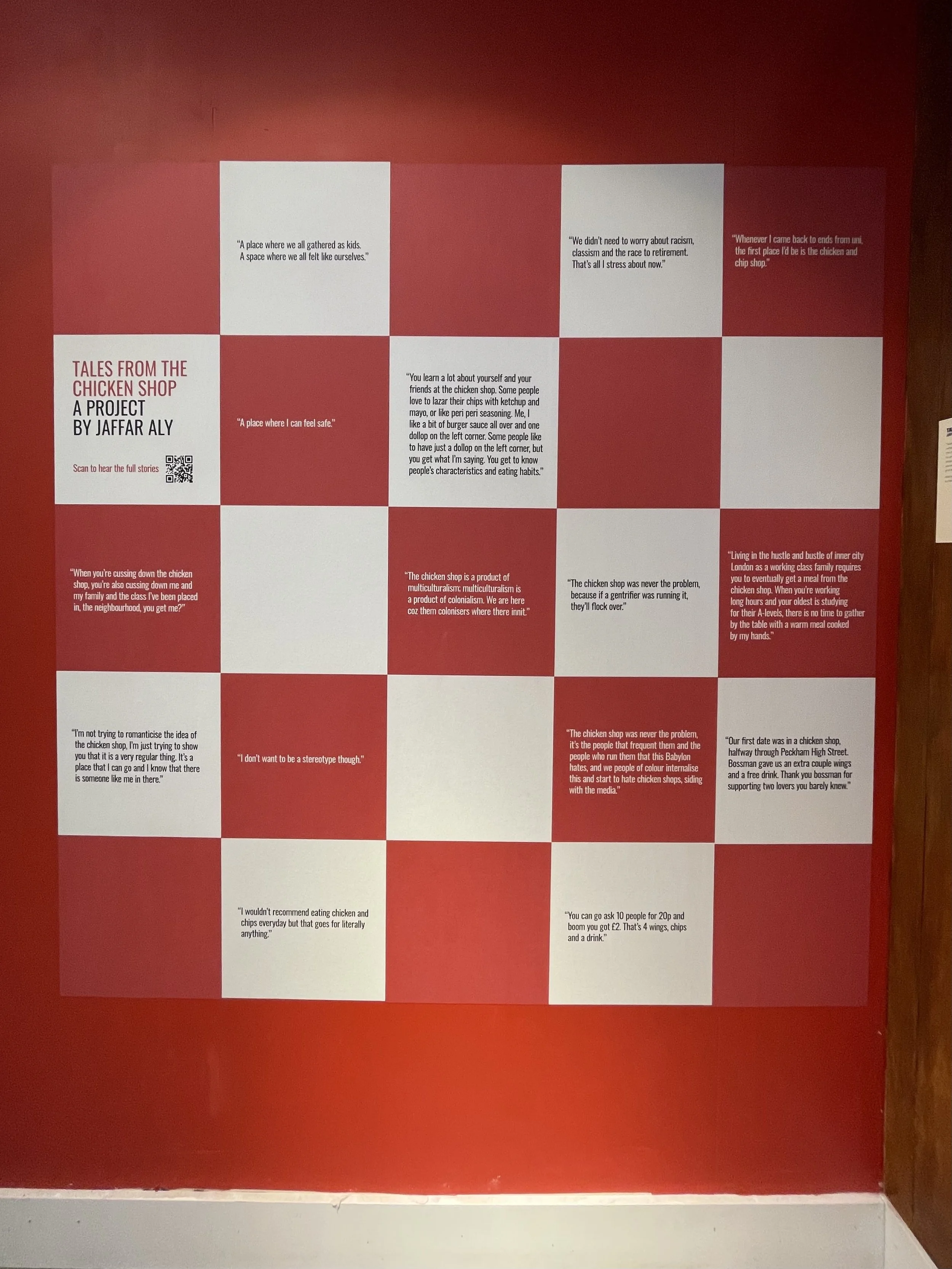

The methodology for this stage of the project has been narrowed down to an art installation as a sight of passive data collection in the Migration Museum in Lewisham. The second is countermapping (M. de Certeau 1984, J. Ackerman 2009, T. Edensor 2010, b hooks 1990) as a form of data presentation and archiving.

Here is a transcription of an audio recording explaining the thought process behind the methodology:

Jaffar: I think I’ve managed to take the project to the next level you know.

Martell: what do you mean?

Jaffar: Like, the project has temporarily been immortalised. It’s become a part of a wider narrative you know. A narrative about diasporic life, assimilation, and marginalisation.

Martell: I hear you, I hear you.

Jaffar: I think the project taking a turn as an art installation acts as a good medium of engagement. You get me. Not only is the art installation there to send out a message, it’s also there as a canonised discussion to some degree.

Martell: I guess so, how are you collecting data?

Jaffar: The installation has a QR code, a public QR code where people outside my circles can interact with.

Martell: Is it working? Are people interacting with it more.

Jaffar: I want to say yess but we will truly know until the show is over next year. So far, I’ve only gotten a few new “data”. A few more than the website. You get me.

Martell: How you displaying this data?

Jaffar: I created a map that highlighted the quotes I’ve been given. Instead of a map that shows you regular map stuff, I wanted to locate chicken shop and show their radius to oneself and others. There are literal stories that can be found in different areas you know. The map is at its infancy, but give it till next year. It will be filled with stories. OMG, it’s a map of stories!

Martell: A map of stories sounds good!

Jaffar: But yeah, that’s how I’m manoeuvring with my methodologies in stage 2 of ‘Tales from the chicken shop’. An art installation and a counter map.

Migration Museum Installation:

The current show at the Migration Museum is titled ‘Taking Care of Business’. An immersive show where they highlight ‘the central role that migrant entrepreneurs have played in shaping our lives.’ (Migration Museum website 2022). Migrant entrepreneurship needs to be celebrated and recognised. The Migration Museum seek to do so.

I got in contact with Aditi Anand, the Artistic Director at the Migration Museum and asked her a few questions surrounding the curation of the current show ‘Taking Care of Business’ and how this project situates itself within the show and how can it be better improved. Here is what she said:

Jaffar: Why did you see it important to include the voices/tales from the chicken shop in the curation of the show?

Aditi: Taking Care of Business focusses on the role that migrant entrepreneurs and businesses play in our lives – from the food we eat, the clothes we wear, the apps on our phones, the essential services we rely on and much more. Chicken shops are integral businesses and community spaces on our high streets, and have historically been founded and run by migrant proprietors. One of the most famous examples of this is the South London institution Morley's, founded by Lewisham based and Sri Lankan born entrepreneur Indran Selvendran. In addition to telling the business owner story, we wanted to include voices and stories from customers of the chicken shop reflecting on what these spaces mean to them. 'Tales from the Chicken Shop' offered a nuanced set of stories/voices that were key to understanding the importance of chicken shops, and moving beyond the stereotypical portrayals offered in the news media and elsewhere.

Jaffar: How does this project situate itself with the rest of the show?

Aditi: Tales from the Chicken Shop is featured in a section on migrant founded food businesses, and in particular takeaways. The section also includes an installation about Chinese takeaways curated by Angela Hui, exploring intergenerational experiences of living and working in these businesses, a graphic reportage piece on a Greek Cypriot family-owned fish and chip shop forced to shut due to gentrification and archival images about German pork butchers in the 19th century who in effect invented the original British takeaway staples of sausages and pork pies. There are many themes within these projects that speak to each other: entrepreneurship as a means of survival in the face of a discriminatory job market, the racism and negative stereotypes sometimes directed at migrant owned businesses (leading to extreme consequences such as in the case of the German takeaways during the First World War) and the ways that migrant owned businesses become essential parts of community life.

Jaffar: Was the minimalist design for the art piece deliberate?

Aditi: Some of the considerations for displaying the piece were practical: There were already quite a lot of audio/video pieces in the Takeaway and food exhibition area and we did not want to overwhelm visitors. We also understand that many of our visitors are passer-by’s and do not necessarily have time to listen to long audio pieces. The quotes from the stories collected were very powerful and we felt they would really speak to audiences if they were presented simply and boldly. We also included a QR code so that people could listen to the full stories on their own devices and in situ as the project intended.

Jaffar: How can this project be improved on?

Aditi: Initially we spoke about an interactive component where people could leave their own thoughts/stories. Due to the constraints of space, we did not manage this. I still believe this would be worth doing to add to the multiplicity of perspectives and voices. I would say that the stories collected so far are rich, nuanced and employ very creative modes of storytelling. I would encourage you to keep collecting and exhibiting, perhaps inside the chicken shops that are featured?

The Migration Museum exercising their ‘soft power’ (H. Mason-Macklin & NAEA Museum 2020 in Meduim.com) as a bastion of knowledge creates a space of engagement with the public which help to decentre Eurocentric as well as imperial narratives. The migration Museum embodies a space and place of active progression. A place that has become a catalyst of discussion, interaction and a space that recognises that ‘sincere and unambiguous acknowledgement of oppression and violence is a critical element in social reconstruction and healing’ (P. Green 2009: 78). The tales of the chicken shop is here to reconstruct the image these businesses have been given, and the Migration Museum is a great tool in helping me do so.

Concluding thoughts:

So, what now? Well, the art installation will be at the Migration Museum till March 2023. All I can do is to give the art installation time to gather data over the year. Aditi also mentioned ways of moving this installation to the public eye by actually placing this installation in the chicken shops I talk so much about. A path has been paved for me to take. Hopefully by next year or two I can work with these businesses to create a campaign that gets rid of the negativity that surrounds them and the people who frequent them.

Stay tuned.

Bibliography:

b. hooks (1990), "Homeplace" Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics, Boston: South End Press. pp. 382-390. Available online: http://abahlali.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/hooks-reading-1.pdf

C. Geertz (1973) In The Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic Books.

C.S. Wilder (2013) Ebony And Ivy: Race, Slavery, and Troubled History of America's Universities, London: Bloomsbury.

Migration Museum. Migration Museum . https://www.migrationmuseum.org/

H. Mason-Macklin & NAEA Museum Education (2020) Museum in Progress: Change and Social Healing at the Columbus Museum of Art, Available at: https://medium.com/viewfinder-reflecting-on-museum-education/museum-in-progress-change-and-social-healing-at-the-columbus-museum-of-art-a001c61c1cb6

J. Ackerman (2009). The Imperial Map: Cartography and the Mastery of Empire. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

L. Back (2016) Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters, London: Goldsmiths Press.

M. de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

M. Douglas (1966), Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Ark Paperbacks.

P. Green (2009) 'The Pivotal Role of Acknowledgement In Social Healing', in P. Gobodo-Madikizela & C. Van Der Merwe (ed.) Memory, Narrative, and Forgiveness: The Perspectives of the Unfinished Journeys of the Past. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 74-97.

S. Hall (1997) ‘The Spectacle of the "Other"’, in Stuart Hall (ed.) Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, pp. 223-79. London: Sage

T. Edensor (2010), “Walking in rhythms: pace, regulation, style and the flow of experience”, Visual Studies, 25/1: 69-79.